So… Stan Lee and William Goldman went in one breath of wind… What can I say about that? Today I’ll focus on Goldman. The Oscar-winner screenwriter died this week from colon cancer and pneumonia and other complications. May he rest in peace. He left us a long legacy: some brilliant scripts and a particular way of doing things. One of my favorite movies is Alan J. Pakula’s ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN. I mentioned it here. It is, of course, a very timely movie, even though it has been here since 1976. It was written by Goldman based on the novel by The Washington Post journalists who helped to crack the Watergate scandal which caused the downfall of Richard Nixon: Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward. In the movie, Bernstein is portrayed by Dustin Hoffman and Woodward by Robert Redford. Two flawless performances under the brilliant Pakula direction. I want to talk a bit about this movie and I was set to make two very distinct points on two very different issues: on character development through dialogues and on the importance of the media for democracy. However, as I spoke already on the second point here, and will definitely speak about it again, let me for today focus on the first point.

I’ve been recently asked how to make characters three-dimensional. It’s an interesting and profound question and not necessarily easy to answer. Of course, you can design character arcs and write the backgrounds and develop all kinds of personal traits. I tend not to do that. They might distract me from the really important stuff like… you know… the story. No, I’m kidding – let’s not treat this issue lightly. What I think is that some scenes demand a specific trait from a character and unless it’s absolutely necessary, I develop the characters when I’m plotting and when I’m writing the scenes themselves. If I can, I will not write backstories – unless they are really necessary. So how do you develop a character in a scene? Most of the time, I learned, there is only one thing needed: intelligence. You make them intelligent characters. Thinking characters. There’s a sequence in the first few minutes of ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN that I particularly like and which shows what I mean. Be advised: I did not read Woodward and Berstein’s book and don’t know what was their creative input and what was Goldman’s. Still, I believe this dialogue sequence to be absolutely brilliant.

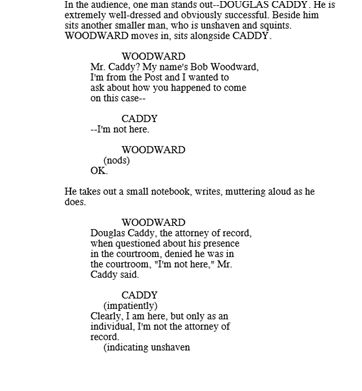

This dialogue goes on between Woodward and a lawyer named Markham, which in the first draft of the script was referred to as Caddy. So here is some of the sequence as written in the script (these are print-screen images, so forgive me for the quality):

I think this simple sequence of dialogues is stunning and utterly revealing for both characters. It’s the first time we see Woodward in action, so it’s his de facto introduction, and even though we never see Caddy/Markham again, it’s a perfectly believable and somewhat developed character – you get the feeling you actually ‘know’ that man from somewhere. The way Goldman did this was by making both characters intelligent (well… one a bit more than the other). So let’s look at the subtext: Woodward is a nosy tenacious reporter and Caddy/Markham is a lawyer trying to avoid the journalist’s questions. He is always trying not to say anything at all, but in fact, because Woodward is intelligent and tenacious, every time he tries to avoid the questions he actually gives more and more away. In the end, with so little said and done, so little of the movie passed, we actually learned a lot about the characters: Caddy/Markham is a somewhat important lawyer with no apparent reason to be there; he is a liar; he was called at the middle of the night; he apparently called the other attorneys himself – he is arrogant, defiant and mysterious, obviously representing some organization or some big shot who wants to be left unnamed. On the other hand, Woodward is a young, ‘hungry’, intelligent reporter who doesn’t quit. It takes about a couple of minutes of the movie for us to learn all this from the characters –without any exposition whatsoever. This is skill. This is Craftsmanship.

You can see this throughout the movie and in several other Goldman’s scripts like BUTCH CASSIDY AND SUNDANCE KID – the way the characters are developed through the intelligence in the dialogue. How can we forget Mandy Patinkin in THE PRINCESS BRIDE saying over and over again: ‘My name is Inigo Montoya, you killed my father, prepare to die!’ Isn’t that the core of that character? Of course, in movie scripts, you have to develop the characters through dialogue – but that can also be done in books, so you ‘show, don’t tell’. It’s still an art form, though, and Goldman was a master at it.

And so William Goldman goes on to a better place. Good for him. He left us better than we were before, which is the vain ambition of many of us. See you around the next campfire.

Pingback: Dialogue Techniques – Part 2 | Hyperjumping

Pingback: Spielberg’s ‘The Post’ and the Banality of Truth and Evil | Hyperjumping